This blog post explores the Freytag Model of narrative. It is the seventh in a series of story structure posts analysing Robert E Howard’s celebrated story, ‘The Tower of the Elephant’, which is summarised here. The previous posts deal with the following models or processes:

The Freytag Model

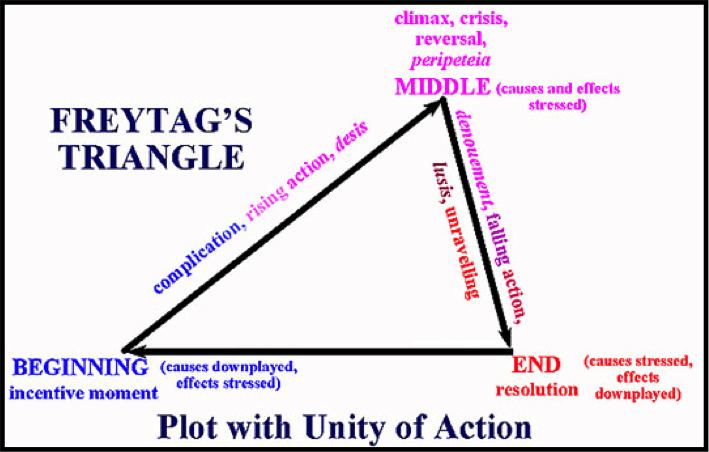

In his book Technique of the Drama (1863), the German critic Gustav Freytag proposed a method for analysing plots. This process is known as Freytag’s Triangle or Freytag’s Pyramid. The diagram below is a version prepared by Barbara F McManus:

Essentially, Freytag’s Model is an example of a five-act story:

- Beginning or Exposition

- Complications/Rising Action

- Climax

- Falling action

- Resolution

‘The Tower of the Elephant’ has three sections, which might suggest the story is in three acts. However, the analysis below, based on the Freytag Triangle, shows both a three-act and five-act story in action.

Section One is divided into two parts. The first part, in omniscient point of view, provides the general setting of the story. This part itself is itself divided into two. The first segment is an establishment shot of the Maul in an unnamed city of Zamora, most likely the capital city. The second one is a closer view of a particular tavern in the Maul.

The second part of Section One is an even closer examination of the tavern. Here, we see characters in dialogue and action, and experience occasional moments inside the Kothian slave trader’s point of view: ‘The Kothian drew back; for the man [the Cimmerian] was not one of any civilized race he knew’.

This section ends with the fight between the unnamed (at this point) Cimmerian and the Kothian. It also ends with the framing of the dramatic question of the story: Will Conan find out the secret of the tower and steal ‘the jewel of Yara’?

In the classic three-act division of a story as Beginning—Middle—End, Section One would be the Beginning. It is also the first stage of the Freytag Triangle: Beginning/Exposition. In some respects, Section One also contains a little of the second Freytag stage, Complications, in that the Cimmerian must overcome the challenge offered by the insulted Kothian: ‘Steel flashed.’ The warrior does this easily.

Section Two involves the Cimmerian’s journey to the tower and his actions in the gardens and the tower itself. The complications explored here include the encounters with the guard, with Taurus the thief, with the lion that was not killed by Taurus’s poison mist, and with the giant black spider that kills Taurus and tries to kill the warrior, whom we now know as Conan. This section aligns with the Middle element of the three-act story and the rising action element of the Freytag Triangle.

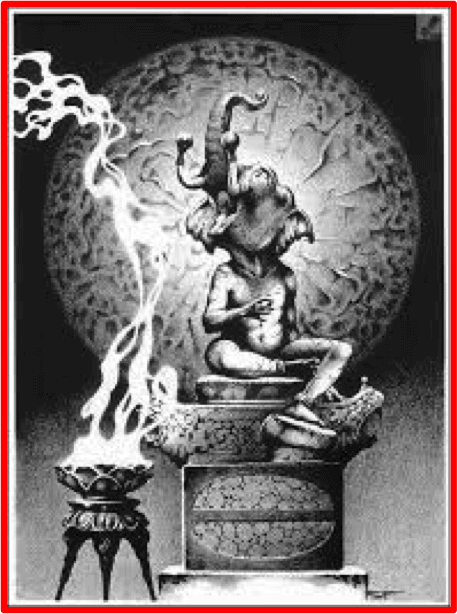

Section Three deals with Conan’s encounter with the living idol, Yag-kosha, his compassion for the idol, his agreement with Yag-kosha’s plan, and his encounter with Yara, in which he sees the fate Yag-kosha, now Yogah of Yag, brings to the high priest.

At the start of this section, virtually all the rising tension has dissipated. Conan has won through to his goal and can now complete his mission and escape. However, he actually discovers the true identity of the idol, which is the true secret of the tower (one of many surprises and reversals in the story): that the idol is not an inanimate statue, is not a god, but is a being from the ‘outer fringe of this universe’ [my emphasis]. This is the proper climax of the story.

In a normal adventure/action story, the climax would be the encounter with the antagonist, the villain, with the remainder of the story recounting the final battle and its after-effects. In ‘The Tower of the Elephant’—and now we see the significance of that title: the story wasn’t called ‘The Wizard’s Tower’ or ‘Yara’s Tower’—the climactical encounter is with the object of the story’s quest, which is not an inanimate treasure, but a long-lived being from beyond.

Here, the dramatic question is answered. Conan is faced with a choice—carry through with his plan or help the unfortunate Yag-kosha. His pity and empathy lead him to make the ‘right’ choice. Yag-kosha is freed, Yara is destroyed, the tower falls, and Zamora is freed of the high priest’s tyranny.

Of course, one might wonder what would have happened if Conan had made the other choice, had ignored Yag-kosha and carried off as much treasure as he could manage. Would he have got past Yara and his guards?

When we first meet Yara, he is deep in meditation and we might assume Conan could have killed the high priest before he awakened. Yet, it is likely the high priest’s ‘power source’ in the room above would have been compelled to warn its ‘master’ of any attack. Conan may not have survived, just like other thieves who had dared to break into the tower. So, in one sense, he had no option but to help Yag-kosha, for to refuse would probably have resulted in his death, even if he did not know this when faced with his decision.

In this third section, which in one sense is the Ending of the three-act story, we have the last elements of the five-act story: the Climax, the Falling Action and the Resolution. In the Climax, Conan encounters Yag-kosha and makes his decision. His brief encounter with Yara is the Falling Action. Although this scene is not the expected hero-villain confrontation, the reader still feels some tension and uncertainty as Conan enters the high priest’s room: how will the warrior handle this encounter and will he survive? Finally, the Resolution features the death of Yara, Conan’s easy escape from the tower, as promised by Yag-kosha, and the collapse of the tower itself moments later.

The above analysis has shown that ‘The Tower of the Element’ can be seen either as a three-act or five-act story, though it hasn’t really provided any insight into the story itself. In other words, all that the analysis has proved is that the structures are relevant; they are descriptive, but not insightful. However, if we refer back to the Freytag diagram and consider its observations about causes and effects, something new does appear.

In the Beginning, the effects of the tower’s and the gem’s existences are emphasised, these being the feelings various characters have about both objects: fear and avarice. At the Climax, which happens when Conan meets Yag-kosha, causes and effects have equal standing. Conan still experiences fear and avarice, but he also learns the true reasons (the causes) of the situation. This new understanding promotes pity and compassion, which lead to his decision to help the strange being, Yogah of Yag. And the Resolution has causes emphasised—the existence of Yara and his magic now nullified—and the effects underplayed: no more fear and avarice.

To be made aware, through the model, of this interplay between causes and effects, and see it in action through ‘The Tower of the Elephant’, is something I hadn’t expected. I can now bring such awareness to my own writing, especially in the construction of story elements relying on hidden causes. I can work to ensure these causes are not revealed until the appropriate moment, which occurs once the effects have played themselves out.

I hope you enjoyed this exploration and can see how to apply the modal, especially the causes and effects relationship, in your own understanding of stories that you read and write.

Be safe, well and inspired!

Cofion gorau (Best wishes)

Earl

______________________________________________________