(The following is based on a chapter of my MA thesis. I wrote this revision a few years ago but never found a home for it. As with last month’s blog post on Imagination, I had forgotten about the piece until recently. Owing to its length, I’ll publish it here in two instalments. I hope you find something stimulating and worthwhile in them.)

As Rogan Taylor shows in his book The Death and Resurrection Show, all artists, both serious and popular, are descendants of the original shamans who helped their tribes understand their place in the cosmos. It was the job of the shaman to be, as Joan Halifax says in Shamanic Voices, ‘the fine tuner of the psyche of his tribe’. Her statement sounds very similar to Shelley’s remark that ‘Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world’ and Ezra Pound’s statement that ‘Artists are the antennae of the race.’

In other words, the shaman’s task was to help everyone in the tribe find answers to their variations of the four great questions (from W. Y. Evans-Wentz, The Tibetan Book of The Dead):

-

- Who, or what am I?

- Why am I here incarnate?

- Whither am I destined?

- Why is there birth and why is there death?

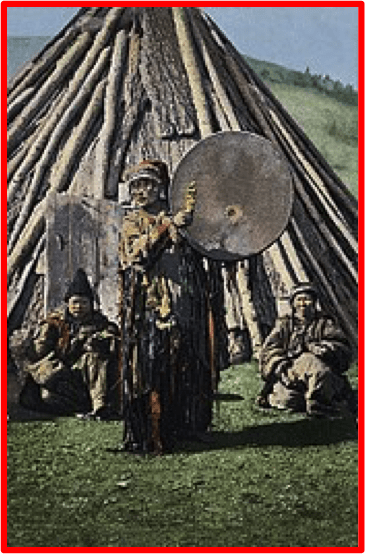

These questions are just as relevant today as they were 100,000+ years ago. The shaman would plunge into the spirit world to recover lost souls or discover ways to improve the spiritual life, and often the material life, of the tribe. They achieved these things through the knowledge of herbs, plants and minerals, etc. gained from the spirits they encountered. In other words, the shaman was a healer and an explorer.

Artists function in the same way today. Those involved in so-called popular entertainment often exhibit the shaman’s healing aspect. One example would be the rest and recuperation offered to the harassed citizen in this rapidly changing post-industrial world when they sit down in front of the TV for a nightly dose of sitcom laughter or reality TV escapism.

Artists engaged in more ‘serious’ pursuits also heal, but more often explore. They have the responsibility of discovering whether or not this world is the one we truly want to live in. If it is, they reveal the benefits of the world, revel in its wonders and grace, and explore its potential. If it isn’t, they help heal our world, help us adapt to it, or explore ways of changing it.

Milan Kundera has stated that he understands and shares Herman Broch’s insistence that ‘The sole raison d’être of a novel is to discover what only the novel can discover’. The novel, as Kundera has also said, is an art that is nothing more than the investigation of man’s being. That is, the novelist is doing what the shaman did (and is still doing nowadays): examining great themes of existence.

However, the shaman’s life was more practical than pure ‘examination’. If the shaman lost the ability to heal tribal members (physically, psychologically or spiritually) or to supply knowledge necessary for the survival of the tribe, his tenure would be short-lived. Artists today are under the same injunction (even if they are unaware of it or choose to ignore it). What effect has the art piece on the tribe of the artist? Does it heal? Does it offer insights or knowledge? Has it some sort of utility?

I would say that art, because of its genesis in the activities of our ancestor shamans, is above all a spiritual tool, and the validity of an art piece is measured by the spiritual effect it produces. Taylor answers the question: ‘What is the essence of all religious enterprise?’ with: ‘It is the secret of the magic of Change itself’. To this he adds, ‘Religion is a tool for both surviving and accomplishing transformation.’

In the profound spiritual vacuum of the twentieth-first century world, with the increasing dislocation of people from themselves and their planet giving rise to nationalistic impulses, runaway self-interest, and irreversible ecological damage, an approach that emphasises the ability to both survive and encourage Change—Good Change (however you define it, a complex question)—is surely required.

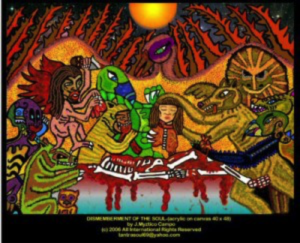

What I’ve said above is primarily about broad artistic approaches. Shamanism, however, also offers an experience that is of particular pertinence to literary production. Many shaman initiates undergo a

‘terrifying descent . . . into the underworld of suffering and death . . . represented by figurative dismemberment, disposal of all bodily liquids, scraping of the flesh from the bones, and removal of the eyes…’ (Halifax)

After such an ordeal, the initiate is established as ‘one who has met death and been reborn’. The shaman then becomes someone who takes on what one Eskimo shaman has called ‘the great task’, becomes someone who can ‘maintain balance in the human community as well as in the relationships between the community and the gods or divine forces that direct the life of the culture’.

All this is well and good. However, I believe that the over-reliance on the authority of the shaman and his descendants in such matters has meant a gradual decay in the power of individuals to access and maintain their own, shall we say, Inner Authority. I also believe that the mission of modern poets (in the broadest sense of the word) should be to provide a means of enabling their readers to gain access once more to their Inner Authority. In this way, they themselves can function in the community and in connection with the divine, whatever form it takes.

The shaman achieves this type of integration through a rite of transformation that usually ‘demands a rending of the individual from all that constitutes his or her own past.’ It seems to me that the only way such a modern integrated self can be constructed, or discovered, is through a similar process of shedding. That is, a literary piece displaying and encouraging this process would contribute to an increased reliance on Inner Authority.

To this end, the plotlines of many literary works do involve the protagonist in a process of dismemberment, whereby his or her psychological world is shattered through various abuses and losses. This dismemberment then triggers a spiritual crisis that might result in the protagonist achieving some sort of self-actualization. As in the shaman’s initiation, the protagonist will retrieve his or her soul through a process of death and re-birth. And the reader will share in this journey and its outcome. A modern shaman, T S Eliot, put it thus in ‘East Coker’ of Four Quartets:

In order to arrive at what you are not

You must go through the way in which you are not

(I hope you’ll find your ‘way’ back here next month for the second instalment of my exploration of shamanism and literary creativity.)

Cofion cynnes (Warm wishes)

Earl

______________________________________________________