(This is the second instalment of an adaptation of a chapter of my MA thesis, which I wrote a few years ago but for which I never found a home. I hope you enjoy it. I’ve repeated several paragraphs from Part One to ease you back into it.)

… I also believe that the mission of modern poets (in the broadest sense of the word) should be to provide a means of enabling their readers to gain access once more to their Inner Authority. In this way, they themselves can function in the community and in connection with the divine, whatever form it takes.

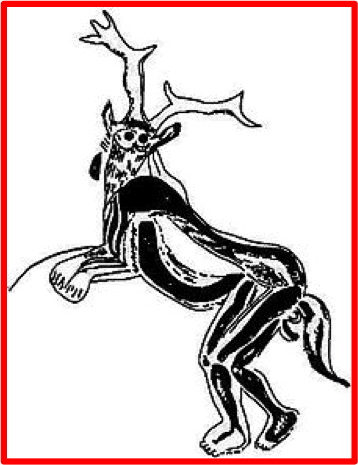

The shaman achieves this type of integration through a rite of transformation that usually ‘demands a rending of the individual from all that constitutes his or her own past.’ It seems to me that the only way such a modern integrated self can be constructed, or discovered, is through a similar process of shedding. That is, a literary piece displaying and encouraging this process would contribute to an increased reliance on Inner Authority.

To this end, the plotlines of many literary works do involve the protagonist in a process of dismemberment, whereby his or her psychological world is shattered through various abuses and losses. This dismemberment then triggers a spiritual crisis that might result in the protagonist achieving some sort of self-actualization. As in the shaman’s initiation, the protagonist will retrieve his or her soul through a process of death and re-birth…

However, it must be remembered that the dismemberment the shaman experiences is only one part of the actual sequence of shamanic initiation. Broadly speaking, a man or woman in becoming a shaman passes through three stages:

- The encounter with the supernatural

- Initial sickness that produces a near-death experience

- Descent into the Underworld: trials, adventures, acquisition of new knowledge, further encounters, capture and dismemberment, magical recovery

- Ascent towards the Upperworld, acquisition of more knowledge

- Joyous return to the Middleworld, with power

- The apprenticeship with an older shaman

- Guidance during further journeys to the other worlds

- Refinement of techniques and teachings learned from the spirits

- The new shaman’s trial-by-performance

- A reproduction of the shaman’s experiences in order to validate them

- A practical demonstration of the shaman’s power over spirits, establishing credentials so that the shaman can continue to shamanise in the community

As the shaman’s resulting life after acceptance by his community would involve further spirit journeys and experiences in shamanising, this ‘after-life’ could be viewed as a fourth stage in the shaman’s ongoing development of abilities and prestige.

It is possible to find literary equivalents for these stages, both in the making of a writer and in the making of a writer’s works, as in the table below (apologies for the messy layout).

SHAMANISM LITERARY LIFE LITERARY WORK

1. Encounter with spirits Inspiration, first books read Inspiration for the work

Initial illness Early childhood illness or abuse Emotion driving the work

Near-death experience Effects of early illness/abuse Facing the blank page

Trials and adventures Life experiences Research and drafting process

Dismemberment Breakdowns/suicide attempts Psychological digging

Magical recovery Writing joy, more experiences Writing Joy, more experiences

Knowledge, techniques Learning of the art and craft New techniques and approaches

2. Apprenticeship Mentors, reading, practise art/craft Research and drafting process

3. Establishing credentials First creative publications/first book Publication, marketing, critics

4. Shamanising Further practice of art and craft On-going ‘healing’ of readers

This table suggests one possible reason most first works of serious fiction are in some way autobiographical. New shamans have to reproduce their initiations and demonstrate the powers obtained during the initiation process in order to convince their tribes they should be allowed to shamanise. In much the same way, first-book authors may have unconsciously realised they need to present the experience of becoming a writer in order to establish the credentials for continuing to write.

Once shamanhood has been established, the shaman can begin to practise within the community. In most cases there is no choice about the matter, as Tiuspiut, a Yakut shaman, describes:

‘ . . . At last I became so seriously ill that I was on the verge of death; but when I started to shamanise, I grew better; and even now, when I do not shamanise for a long time, I am liable to be ill.’

This is true of artists also, as Eliot, yet again, has so succinctly observed:

Anyone who has ever been visited by the Muse is thenceforth haunted.

In summation, the benefits of shamanising depend on two recognitions:

- That the cure of the shamans’ on-going sicknesses ‘demands that they dramatically share their experience of transformation simply to remain healthy themselves’.

- That the ‘shaman’s sickness is, in reality, everybody’s sickness’, which is to do with Change, which ‘causes terror . . . is . . . Inevitable . . . Unavoidable.’

Thus, during the shamanising,

‘The shaman’s main healing effort appears to be directed at producing a similar ecstatic condition not only for himself, but also in the patient, if at all possible, and by no means least of all, in everyone gathered for the occasion. His cure is a cure for the general human condition, and it is directed at everybody. Everybody is sick and, in the shaman’s healing séance, everybody gets better.’

Since the goal of the ceremony is to reproduce the shaman’s original ecstatic experience of descent into the Underworld and flight through the Upperworld, each healing ceremony would involve the same pattern of experiences. Given that the shaman is the writer’s ancestor, this pattern, as shown in the table above, could also be used as a structure for any literary work.

All artists, either consciously or unconsciously, adopt a model explaining the usefulness of their art to themselves and to others, though they may not be fully aware of the historical heritage of the model they have formed and its attendant responsibilities.

I hope this essay has revealed the extent modern artists rely on the spiritual foundations and tools of their shaman predecessors. I also hope such artists will accept the responsibility for producing the spiritual effects that this awareness now entails. In doing so, they will help their culture, their ‘tribe’, find answers to those questions posed in Part One, which are all about dealing with Change:

- Who, or what am I?

- Why am I here incarnate?

- Whither am I destined?

- Why is there birth and why is there death?

Cofion gorau (Best wishes)

Earl

______________________________________________________