In Joan Didion’s collection of essays, The White Album (1979), the first line of the title essay is ‘We tell ourselves stories in order to live’, a line that made that essay famous. And it is true. Stories exist to help us live, or why else would the storytelling function survive through thousands, millions, of years of evolution. The first storytellers commemorated the hunt and how to be successful while avoiding the dangers involved. Or they told of the way stars and nature indicated the change of seasons and the food sources that came with them. Stories about how to survive. How to thrive. How to live well and pass on that knowledge to the next generation.

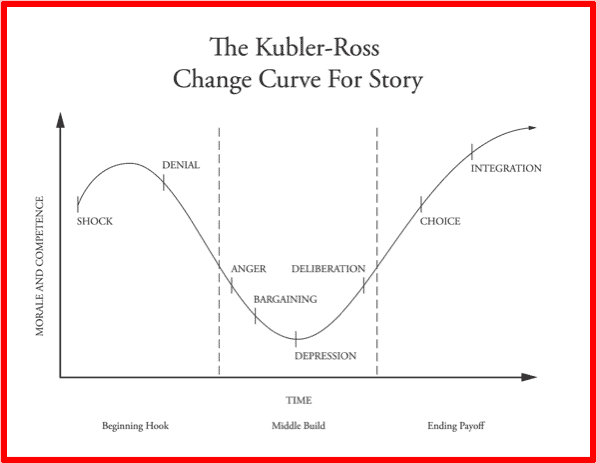

As Shawn Coyne notes in essays discussing his Story Grid methodology, ‘Stories give us scripts to follow’ and story is a ‘coping with change’ narrative.

The keyword that jumps out to me is ‘change’. Stories help us deal with change, which is ever-present. Birth. Growing up. Finding one’s place in the world. Building something worthwhile in the world. Dealing with threats (physical, emotional, financial, spiritual) to oneself and one’s loved ones. Experiencing and learning to accept death. Stories, personal and collective, in all forms (poems, fiction, non-fiction, plays, films, hypertexts, etc.) give us models of action and behaviour for dealing with the challenges we all face.

It seems to me that, as a rough guide, there are three types of stories: stories of doing, of being, and of becoming. ‘Doing’ refers to those stories that are about achieving something in the world, about dealing with or creating change. Primarily, these stories involve a character who does not change—think of John McClane in the Die Hard movies, James Bond, and the Marvel and DC superhero franchises. Maybe a character changes internally in a small way in order to help effect or correct the big change in the external world, but the emphasis is on the healing of the disruption in the world or the creation of a new, better world.

Stories of ‘Being’ would involve an emphasis on internal change. These may involve a character going through some rite of passage (coming of age, for example) or a character changing their role in the ‘society’ around them, whether a family or a corporation. Examples would be Jane Austen’s stories, Anna Karenina, The Great Gatsby, Saturday Night Fever.

For both these categories, I am reminded of Orson Scott Card’s MICE quotient, his categorisation of story types, as explained in my blog post Story Process 2:

- M = Milieu, stories that explore a new world of some sort (Lord of the Rings, Moulin Rouge). These would be mainly ‘Doing’, though if the character exploring the world decides to stay that decision may involve the character changing in some way, hence ‘Being’.

- I = Idea, stories that solve a mystery, as in police procedurals. Generally, such stories would also be ‘Doing’.

- C = Character, stories that show a character growing out of an old role or into a new role. These would be predominantly ‘Being’.

- E = Event, stories that involve the repair of a disruption to the world. As with Milieu stories, Event stories might require a combination of ‘Doing’ and ‘Being’, with the former dominating.

Both ‘Doing’ and ‘Being’ involve something akin to what the transpersonal philosopher Ken Wilber calls ‘translation’, a type of horizontal change, like shifting the furniture in your house to make it more comfortable in some way. However, your house may have many levels, from the basement through a number of floors to the attic, the house of your mind, so to speak (an extension of a metaphor Jung explored through the dreams he reported in Memories, Dreams, Reflections). And so, there is another type of change, in a vertical direction, which Wilber calls ‘transformation’. Here, you go from one level of your house to another, a change in consciousness, which thus leads to my last category, ‘Becoming’.

‘Becoming’ refers to those stories involving the complete transformation of the character into something bigger than the self, or into some other sort of being. Examples of such stories would be Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (which was only loosely based on Arthur C Clarke’s story ‘The Sentinel’, as the author himself was at pains to state).

It could be argued that the character arc for Paul Atreides in Frank Herbert’s Dune (possibly the greatest science fiction novel ever) involves ‘Becoming’, in that he transforms from an avenger of his father’s murder to something much greater, a messiah for a cause that changes the universe in a monumental way, even though he is also considered a tyrant. He becomes bigger than his initial desire and abilities. As Herbert once said in an interview, Paul is someone ‘real in the flesh and blood sense who by the process of emulation becomes something larger than life, far larger than life’. The book itself is an exploration of ‘as many permutations as I could recognize in the process’.

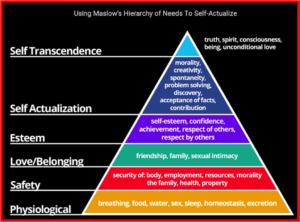

Another way of looking at these three types of story is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which I briefly explored in a previous post:

As a rough division, ‘Doing’ would involve the Physiological and Safety levels, ‘Being’, the Love/Belonging, Esteem and Self-Actualization levels, and ‘Becoming’, the Self-Transcendence level. There is likely to be overlap, as I indicated above, if a story involves a mix of external and internal dynamics. For example, Frodo in The Lord of the Rings is so transformed by his journey from simple hobbit to wounded hero that he is unable to stay in the world he helped to save.

So, next time you’re reading/watching a story, you might try to figure out which category the story belongs to and how this helps you unpack its meaning.

Thanks for reading. If you have any thoughts about my three categories (I’m always up for a ‘robust’ discussion) or you have a particular story you think is an exemplar for one of them, please let me know in the comments section.

Stay safe, healthy, sane and inspired!

Hwyl am y tro (Bye for now)

Earl

______________________________________________________