More Robert Heinlein Insights

In a post earlier this month, I looked at Robert Heinlein’s ‘Five Rules for Writing’. These rules were listed almost as an afterthought in an article he wrote for Of Worlds Beyond (1965), a symposium of essays by leading SF writers of the day about their experiences in the field. The main part of Heinlein’s article (‘On the Writing of Speculative Fiction’) featured an analysis of what a story is, what SF is, and what types of SF stories exist.

The first paragraph tells us ‘there are at least two principal ways to write speculative fiction—write about people, or write about gadgets’ and that most ‘science fiction stories are a mixture of the two types’. Heinlein then dismisses the gadget story to concentrate for the rest of the article on the human-interest story, which is the type he writes.

Several paragraphs later, he supplies a definition of story:

A story is an account which is not necessarily true but which is interesting to read.

As he admits, this definition is quite general and covers ‘all writers, all stories—even James Joyce, if you find his stuff interesting (I don’t!)’.

He also lists what he considers are the three main plots for the human-interest story:

- Boy-meets-girl (with all its varieties: ‘boy-fails-to-meet girl, boy-meets-girl-too-late, boy-meets-too-many-girls, boy-loses-girl, boy-and-girl-renounce-love-for-higher-purpose).

- The Little Tailor, which are ‘all stories about the little guy who becomes a big shot, or vice versa’. Some examples he gives are ‘Dick Whittington’, David in the Old Testament, and Galactic Patrol (but not Grey Lensman).

- The-man-who-learned-better, the story of a ‘man who has one opinion, point of view, or evaluation at the beginning of the story, then acquires a new opinion or evaluation as a result of having his nose rubbed in some harsh facts’. His examples include A Christmas Carol and his own ‘Universe’ and ‘Logic of Empire’. (Heinlein didn’t realise he was writing this type of story until L. Ron Hubbard pointed out the structure to him.)

The type of story Heinlein wants to write—something-interesting-but-not-necessarily-true—is limited to a particular recipe: ‘a man finds himself in circumstances that create a problem for him’. In order to cope with the problem, ‘the man is changed in some fashion inside himself’ and the story ends ‘when the inner change is complete’.

After all his analysis of ‘what a story is and how to write one’, he gathers up the bits and defines ‘the Simon-pure science fiction story’:

- The conditions must be, in some respect, different from here-and-now, although the difference may lie only in an invention made in the course of the story.

- The new conditions must be an essential part of the story.

- The problem itself—the ‘plot’—must be a human

- The human problem must be one which is created by, or indispensably affected by, the new conditions.

- And lastly, no established fact shall be violated, and, furthermore, when the story requires that a theory contrary to present accepted theory be used, the new theory should be rendered reasonably plausible and it must include and explain established facts as satisfactorily as the one the author saw fit to junk. It may be far-fetched, it may seem fantastic, but it must not be at variance with observed facts…

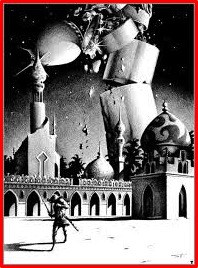

Can any of the above be applied to ‘The Tower of the Elephant’? Below are Heinlein’s ‘bits’ in relation to the story, as I see them.

Definition of a Story

Certainly, ‘The Tower of the Elephant’ isn’t ‘true’, in that it is set in the imaginary Hyborian Age, and is also ‘interesting to read’. I suspect, though, that people who find James Joyce interesting may not necessarily find Robert E Howard’s works interesting, and vice versa.

Story Plot

There is no ‘boy-meets-girl’ scenario and Conan is not a ‘Little Tailor’, at least in this tale, though in others he does achieve great things. ‘The Tower of the Elephant’ is a type of ‘the-man-who-learned-better’ story, in that Conan learns more about his universe, because of what Yag-kosha tells him, and more about himself, in his development of compassion for the otherworldly being and its plight.

The Simon-Pure Science Fiction Story

Although ‘The Tower of the Elephant’ is a fantasy story rather than a science fiction one, we can still evaluate Heinlein’s list against it:

- The Conditions: The Hyborian Age is completely different from the here-and-now, as are the existence of otherworld beings, magic and giant spiders.

- Essential to the story: Without the Hyborian Age and the possibility of magic and otherworld beings, the story could not exist. These elements actually determine the background and context of the story and help provide the conflict and the resolution.

- Human Problem: At first, Conan’s problem is how to steal the Elephant’s Jewel. He takes on this challenge out of pride and, quite likely, because he needs funds to live. This problem comes out of the situation of the story: a barbarian leaving his native lands and moving into civilisation, yet not understanding, appreciating or liking the nuances of civilised life. Conan is an adventurer trying to make his way in the wider world. The situation, however, morphs into a deeper human problem, that of choosing between his own needs and that of another being.

- The human problem created by the conditions: The situation of Yag-kosha needing Conan to ‘rescue’ him has definitely been created by the initial condition of Yara, ‘versed in dark knowledge’, enslaving the otherworld being Yag-kosha. This situation leads to the human choice Conan faces: be selfish or selfless.

- No Violation of Facts: As the story is a fantasy set in an imaginary world that has its own rules and is not therefore science fiction (even though the idea of other universes is used) means that this list element is not applicable.

In summary, because of the conditions of his world and the situation involving Yara and Yag-kosha, Conan encounters a problem—the need to decide between his original mission of robbery and a new mission of rescue. Conan changes from a young adventurer marked with the ‘clean, lean fierceness of the wastelands’ to a more mature warrior, mature because of increased knowledge of the world and of himself. He develops (or uncovers) empathy and compassion. He grows and will never be the same. And with this completion of inner change, the story ends. Conan escapes as Yara’s tower collapses. Conan’s world has changed both externally and internally.

As with the writing rules described in my previous blog, this consideration of Heinlein’s approach to the writing of speculative fiction is possibly more useful for writers than for readers. However, a reader of any genre of story can benefit from his ideas, especially if they use these ideas to ask questions:

- What sort of human-interest story is it?

- What problem does the character face?

- Does the problem arise from the conditions of the particular world, and how does this happen?

- Is it a story of ‘character, rather than incident’? That is, is the problem a human one?

- Why does the character face this problem?

- Does the solution to the problem require the character to change?

- What sort of change?

I hope you enjoyed this application of Heinlein’s storytelling insights to ‘The Tower of the Elephant’. If you have any comments about the post, do let me know. Thanks.

Stay safe, sane and inspired!

Cofion Cynnes (Warm Wishes)

Earl

______________________________________________________

One Comment