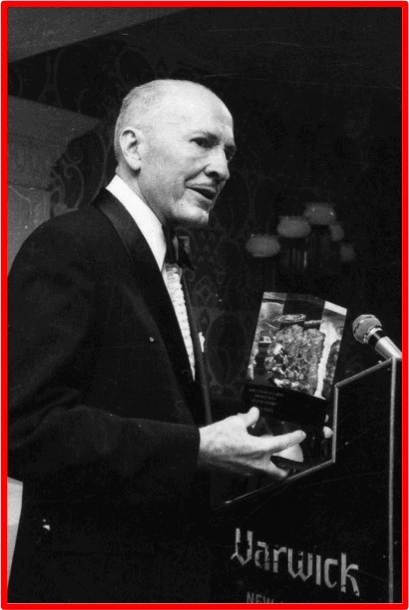

(Robert Heinlein, named as the first Science Fiction Writers Grand Master in 1974.)

Along with Arthur C Clarke and Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein is considered one of the true greats of science fiction. Heinlein published 32 novels, 59 short stories, and 16 collections. Four films (including Starship Troopers and Predestination) and two television series have been based on his work. My favourites of his novels are the standout Stranger in a Strange Land and the under-rated The Moon is a Harsh Mistress.

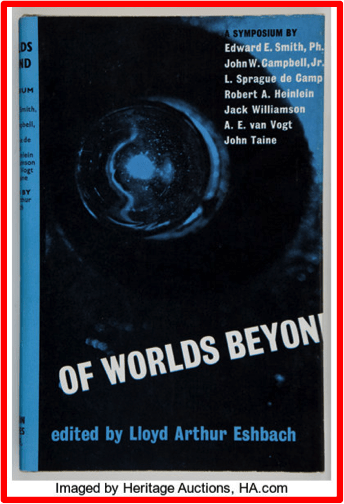

Heinlein is sometimes called ‘the dean of science fiction writers’, partly because of his mentoring of and his influence on writers such as Ray Bradbury and Spider Robinson. In his book Between Planets, Heinlein popularised the concept of ‘pay it forward’ and encouraged those writers he helped to help others in turn. One way he practised what he preached was his listing in an article, ‘On the Writing of Speculative Fiction’ (published in Of Worlds Beyond) five business habits, five ‘practical, tested rules which, if followed meticulously, will prove rewarding to any writer’.

If you’re not someone who is interested in pursuing a writing career, I hope the following exploration of Heinlein’s Five Rules will give you something to think about in relation to your own endeavours. If you are pursing a writing career, I’m sure the rules will help you succeed, though they are not as simple as they look.

1. You must write.

This is obvious. You can’t be a writer if you haven’t written anything. If you only talk about being a writer, but don’t actually find, or more importantly, make time for your writing, then you will never be a writer. Using the comparison Robert J Sawyer introduced in his own article on Heinlein’s rules, if there are 100 people aspiring to be writers, maybe only half of them will actually apply themselves to the work itself. The other 50 will bask in the supposed glory of being a writer who is always getting ready to write.

2. You must finish what you start.

Again, this is obvious. If you keep starting stories or poems or scripts and abandoning them every time you get stuck (for whatever reason), then jump into something new and exciting, only to abandon it in turn, you will never finish any of them. I suppose technically you could still call yourself a writer, because you are actually writing something, but without a finished piece, no one else will know. Again, that may be fine with you and you will join the 24 other writers out of 50 who never finish what they start. That leaves 25 who do.

3. You must refrain from rewriting, except to editorial order.

This is where things become interesting. Some writers have taken this rule as an encouragement to not rewrite at all. Here is Dean Wesley Smith in his book Writing into the Dark:

Truth: The biggest waste of time in writing is rewriting. Period.

Huh? So, all those years writers like Joyce and Hemingway spent working on their masterpieces was wasted? Their books are still in print after almost a century. Will the same be said of those writers who don’t heed Hemingway’s statement that ‘The first draft of anything is shit’?

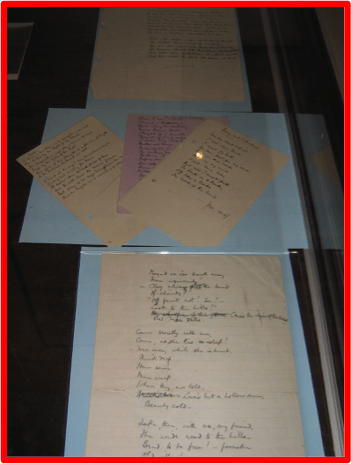

I remember being at a poetry reading and one poet standing up during the open mic session and proudly stating they had written 300 poems in the last month. Three hundred first drafts maybe, but not 300 completed poems. In the Dylan Thomas Centre (Canolfan Dylan Thomas) in Swansea, Wales (Abertawe, Cymru), there is a cabinet displaying several worksheets (see photo) out of the 200 that Thomas wrote while refining a line in one of his famous poems. That’s rewriting. That’s working at one’s craft until the poem is ‘right’.

(Author photo)

(Author photo)

To be fair, maybe some of those who think rewriting is a waste of time are actually doing something other than putting their first drafts out there (which many do through some form of indie publishing). What I find intriguing and ironic about Dean Wesley Smith’s approach is that later in his book he describes a technique called ‘cycling’, which he uses whenever he has become stuck in his writing:

I instantly jump out of the timeline of the story and cycle back to the first word and start through the story again. Sometimes I add in stuff, sometimes I take out, sometimes I just reread, scanning forward, fixing any mistakes I see… So when I get back to the white space, I have some speed up and I power onward, usually another 500 or so words until I stop. Then I cycle back again to the beginning and do the same thing, run through it all until I get back to the white space with momentum and power forward again for another 500 or 700 words.

If this isn’t a form of rewriting—adding in, taking out, fixing mistakes—then I don’t know what else to call it. However, what might be happening here is some sort of semantic confusion. What Smith considers rewriting might be what others call redrafting: going through the manuscript once it is finished and adding, taking out, fixing. And for some writers this may take several redrafts. Here’s Alan Garner, ‘the most important British writer of fantasy since Tolkien’ (Philip Pullman), who describes his drafting process in a 1968 article that is quoted in First Light:

The first draft is in longhand, revised to the point of illegibility, and the resulting mess is typed, some revision taking place on the typewriter. This first draft is corrected, and when it is as good as it can be made [that is, it is finished], a clean, second typescript is prepared, corrected and sent to the publisher…

Smith, however, aims to have a complete single draft by the time he finishes his process, a draft he presuambly doesn’t return to unless under ‘editorial order’. Yet, to get such a functional and completed ‘first draft’ he and those others who follow the cycling method have gone through that draft multiple times. This is just rewriting in disguise.

But back to Heinlein’s third rule. What I really think it means is that once your piece is sufficiently finished, you shouldn’t continue tinkering with it, which is something you could do forever. (To modify Paul Valery: A piece is never finished; it is only abandoned.) However, if an editor asks for changes, because they’ve seen something you haven’t or because they know something about the market that you don’t, then go at it, if you are in agreement. This has certainly been my experience with a couple of short stories published this year.

Of the 25 remaining aspiring writers, 12 are still redrafting/editing/rewriting and 12 have ‘finished’. (Don’t ask about the 25th writer. Maybe his name is Schrodinger and he and his cat are quantum-stuck in both camps.)

4. You must put it on the market.

Now we’re back to the obvious. If you want to be a published writer, then you have to send it out to magazines, journals, book publishers. Alternatively, you could publish it yourself using any number of platforms, either digitally or in print or both. Either way, you need to put your piece out there and await the verdict of those who will pass judgement on it: editors, publishers, readers, critics, reviewers. This can be scary, but it is a necessary step to your career as a writer.

Of the 12 writers still in the game, six have sent out their writing and are waiting to hear back, their hearts in their mouths, and the other six are waiting for someone to knock at the door and ask for their masterpieces, or maybe are just content to write for themselves.

5. You must keep it on the market until sold.

To follow this rule, you need to develop a thick skin. Your pieces will be rejected. No two ways about it. But if they are good enough, they will eventually find a home, though you may need to send them out multiple times to achieve this. Believe in yourself and your work and you will succeed.

As for the handling of rejections, the best advice I ever received was from the fine Australian short story writer and novelist Janette Turner Hospital, in a workshop she gave at La Trobe University years ago. This was in the days when you posted out your submission and enclosed a stamped, self-addressed envelope (SSAE) for the answer. Below is the process:

- You go to your letterbox and find one of your SSAEs.

- You take it to your study, pour a glass of your favourite drink, and open the letter.

- If the answer is an acceptance, you drain the glass, run around the room pumping your fist and yelling out ‘Yes, yes, yes’, then sit down at your desk and start (or continue writing/rewriting) another piece.

- If the answer is a rejection, you drain your glass, run around the room yelling ‘Fuck, fuck fuck!’, then sit down and figure out where to send your piece next, preferably on the same day. You then return to your next piece.

The same process is just as useful in these days of email submissions. Just make sure you pour your drink before you open the email.

Of the six remaining aspiring writers, three have been enjoying a glass of their favourite tipple multiple times as they build up their folders of rejections and acceptances. The other three are still dreaming about publication instead of working their way through their fear of rejection.

6. Start working on something else.

As implied in the previous section, once you have a piece out there you should immediately start work on something new. This is not one of Heinlein’s rules but an addition by Robert J Sawyer.

If you think your first finished piece will bring you fame and fortune then, as they say, you’re dreaming. Not many writers achieve such a distinction with their first publication, not unless they’ve served a long, arduous apprenticeship in some way. In fact, not many writers achieve much fame and fortune at all. If that’s the only reason you began writing in the first place, then you’re probably one of the 98 writers who have already given up.

Writers write because they cannot not write. They are process-driven rather than goal-driven. They enjoy the process. They are keen to learn more about the process. They want to ‘get it right’, whatever ‘it’ is. Heinlein says that his five rules ‘are amazingly hard to follow’ but if you follow them (plus Sawyer’s sixth rule), you will become one of the few professional writers out there. That is, you won’t be one of the 98 wannabes but one of the remaining two who have the commitment, perseverance and drive to actually write something that someone else will buy and appreciate.

Write. Finish. Don’t tinker endlessly. Send out. Send out till acceptance.

Write something else. Repeat.

Thanks for reading. Stay safe, healthy, sane and inspired!

Hwyl am y tro (Bye for now)

Earl

______________________________________________________

One Comment